UK Treaties and Alliances – the New Dilemmas of the 21st Century

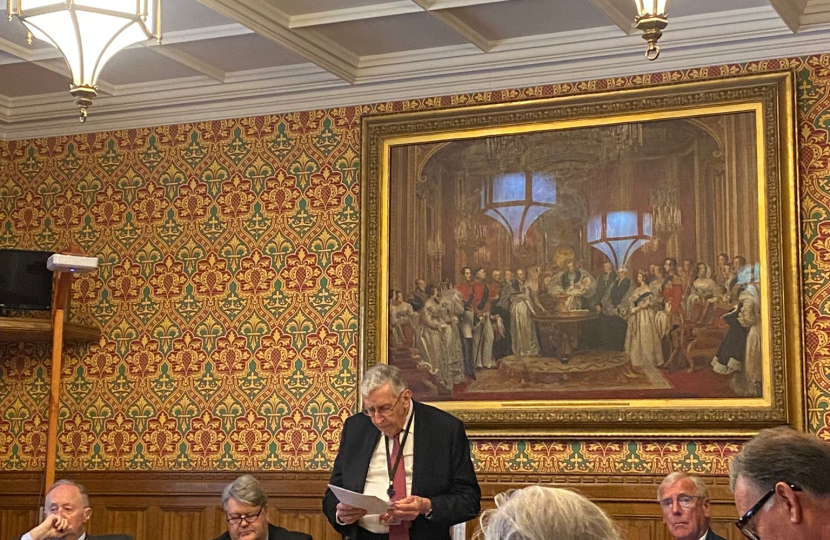

On 22 April the Rt Hon Lord Howell of Guildford – a patron of the Conservative Foreign & Commonwealth Council – gave an impassioned talk to the group’s members regarding the struggle to define a British geopolitical strategy which best serves the UK’s national interests. This struggle can readily be evidenced by the split in strategic thought between those who seek a closer re-engagement with the European continent - and with it, the European Union – and those who seek to tether our strategic priorities to those shared by Washington, as our alliance with the United States remains above all others to ensure our national interests.

However, these traditionalist viewpoints shared within many of the UK’s institutions often fail to adequately deal with the emerging threats facing Britain’s economic and security interests. In particular, the emergence of the digitalised and hyper-interconnected age, in which states must carefully craft strategy and foreign relations, levels new barriers against politicians and policy makers to distil clear statements of a nation’s purpose and direction – making it all but impossible to keep British grand strategy under the roof of one singular Department of State.

Central to Lord Howell’s thesis is the assertion that a central lack of understanding over the way this new digitalised world operates, and how the UK fits into and adjusts to it accordingly, is magnified by this age of internet governance, and the lack of an appreciation of the often malign forces operating across this space. All of which weakens a liberal democratic state’s ability to focus on grand strategy, causing disturbance and dislocation to an entire foreign policy stance.

One readily available remedy to this theoretical upheaval caused by an increasingly polarised and fractious digitalised order is the Commonwealth of Nations, one of the oldest surviving alliances among mostly democratic nations, and located across every continent on the globe. Indeed, whilst many of the 56 member states share similar democratic values and governance structures, one of the real strengths of the Commonwealth is its breadth and depth of membership – ranging from the most populous country on earth – India and its 1.4 billion citizens, to one of the smallest, the 10,000 inhabitants of Tuvalu. Included in this breadth of nations are Canada and Australia, thereby underscoring how the Commonwealth – as a network of like-minded allies and partners – transcends traditionalist ideas of ‘east’ and ‘west’, even of so-called ‘developing’ countries.

Indeed, the fundamental values inherent in the Commonwealth Charter remain as salient today as they did in its outset in 1931, and remain as steadfast in 2024 despite the complexities of a multipolar world of shifting alliances and competing interests. And whilst many foreign policy strategists will continue to call for improved relation with our closest neighbours in Europe, or with the United States which remains one of our most important allies, a modern Britain should not see itself as bound to either entity when it comes to global positioning, and that in fact our interests and potential should go far wider.

This ambitious thinking was best exemplified by our late Queen Elizabeth II, who clearly set out a vision for Britian’s future during her 2009 Christmas Dat broadcast, in which she confidently declared that ‘”In lots of ways (the Commonwealth is) the face of the future”. A bold critique of American misunderstandings of the new world, and an equally bold critique of the wrong direction in which too many are still trying to take the EU, leaves a constructive UK at the heart of a global network of like-minded allies with shared values amongst the Commonwealth, and with many more partnered nations who aspire to Commonwealth membership.

The UK’s most prudent strategy is one of maintaining a balanced role as a good club member of a reformed Europe, keeping a sound but carefully calibrated friendship with America, whilst sustaining its pivotal membership of the Commonwealth – which is fast emerging as the perfect resilient and flexible model for effective 21st Century global relationships. As dangers to the UK’s national interests – and those of our partners – mount daily, hopefully this understanding will come sooner rather than later. Then, truly, the UK may be in a better position to ‘take back control’.

Robert Clark is the Defence and Foreign Policy Director at Curia UK. Robert is also a Senior Fellow at Civitas. He can be found on ‘X’ at @RobertClark87